Achieving the Human Right: Water for All

Jonathan K London, UC Davis Department of Human Ecology

Keywords: Human Rights; Water Justice; California; Community

How do you make your morning Joe? Chances are, you start by turning on the faucet and filling your coffee machine with safe and clean drinking water.

But imagine that nitrates, arsenic, uranium, or other hazardous substances contaminate your tap water instead. You may be paying high water rates for this toxic brew. But you still need to stock up on bottled water, which can easily run over a dollar per gallon, depending on how and where you buy it. It is also not regulated as strictly as tap water. And making coffee is just the first in a long list of daily tasks. Soon, you’ll need to fix meals, wash dishes, bathe your children, and brush your teeth -- all using whatever clean water you can muster.

Does it sound like a scenario from the developing world? Think closer to home. Hundreds of thousands of Californians living in Disadvantaged Unincorporated Communities (DUCs) face these daily challenges. Located throughout the state, DUCs are predominantly low-income communities outside formal city boundaries. Their residents lack city government and basic services, often including safe and reliable water supplies.

Paradoxically, California is a national leader when it comes to proclaiming water equity. In 2012, following years of pressure from environmental justice organizations, Governor Jerry Brown signed a bill making California the first state in the country to recognize a Human Right to Water. Assembly Bill 685 stated,

“Every human being has the right to safe, clean, affordable, and accessible water adequate for human consumption, cooking, and sanitary purposes.”

But this vision has yet to be realized for all Californians. Over the past five years, my colleagues and I from the UC Davis Center for Regional Change and a group of inspiring water justice advocates developed a report on water conditions in DUCs in the San Joaquin Valley, the state’s agricultural heartland, where problems are especially severe.

The report presents a number of sobering findings. Nearly 25% of the 155 community water systems in the Valley serve DUCs and provide unsafe water. This directly affects as many as 30,000 DUC residents. An additional 120,000 residents may be served by unsafe water because they are only partially overlapped by a CWS providing safe drinking water. This includes 27,000 DUC residents without access to community water systems and maybe drinking untreated and unregulated private well water.

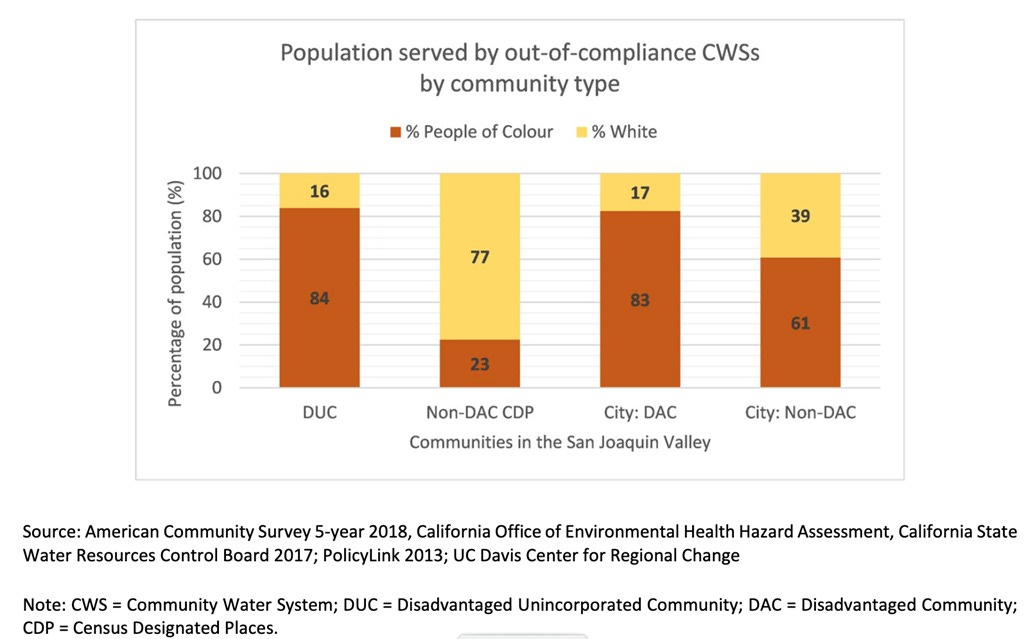

We also found racial and ethnic disparities at work. Latinos, who account for just under half of the total population of the San Joaquin Valley, make up over two-thirds of DUC residents. Of all valley residents served by out-of-compliance water systems, 84% are people of color, while only 16% are white.

These patterns stem from decades of discriminatory land use policies and planning by cities, counties, and water boards, which have adversely affected people of color for generations.

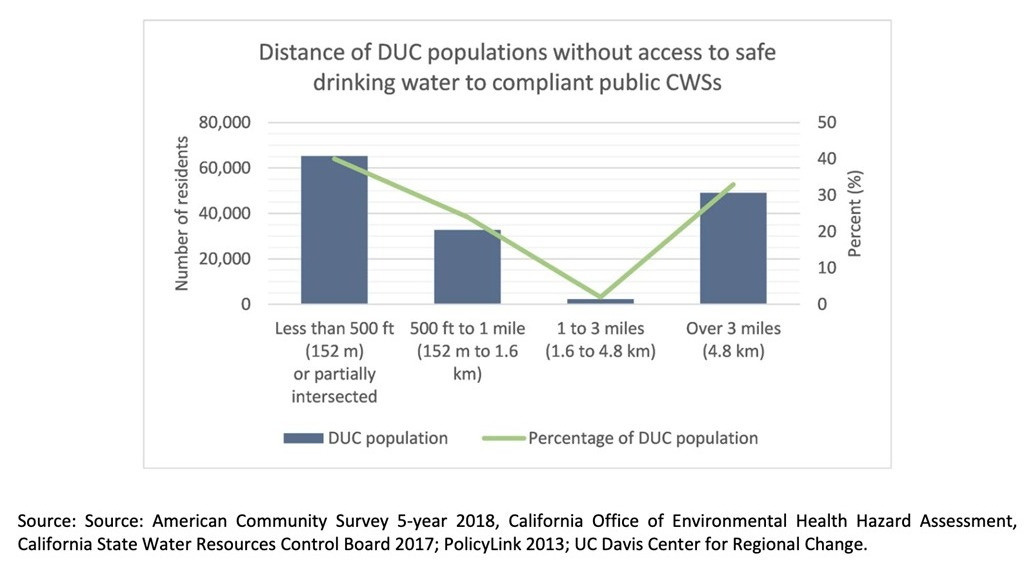

The good news is that for many DUC residents, safe drinking water is often close at hand. Two-thirds of DUC residents live close to a community water system that does or could provide safe, clean water, given the proper investments in infrastructure. Of the 150,000 DUC residents who are not served by a community water system, 44% live within 500 feet of a community water system boundary, while another 22% live within one mile of a safe drinking water supply.

For the majority of DUCS, water system consolidation or service extension is thus both physically and economically feasible. This tells us that the Human Right to Water not only should but can be upheld for DUC residents in the San Joaquin Valley and elsewhere in California.

To do this, our report offered several common-sense recommendations. First, the state should develop and strengthen mandates and incentives for community water systems to serve DUCs. Second, it should create larger, more stable, more equitably distributed, and coordinated funding sources to correct historical patterns of inequitable access to resources. Third, the state should require local governments to comply with existing land use and annexation laws to address the legacies of discriminatory local planning practices. Lastly, it should invest in providing new, publicly accessible data and mapping tools to improve local and regional planning.

Fortunately, in the years since the publication of our report and paper and driven by the powerful voices of water justice advocates such as the Community Water Center and Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability, the state has indeed moved on many of these policy recommendations. Most notably, the Safe and Affordable Funding for Equity and Resilience (SAFER) Act, passed in 2019, dedicates over $1.3 billion to invest in clean water infrastructure in disadvantaged communities throughout the state.

California has led the nation in codifying a Human Right to Water. Now is the time to make this promise a reality. We call on our elected officials and civic leaders to continue to ensure that all Californians enjoy this basic right every morning of every day – starting with that first cup of coffee.

The full report, titled The Struggle for Water Justice in the San Joaquin Valley: A Focus on Disadvantaged Unincorporated Communities, can be accessed on the center’s website: https://regionalchange.ucdavis.edu/report/the-struggle-for-water-justice. The peer-reviewed paper is London, Jonathan K., et al. "Disadvantaged unincorporated communities and the struggle for water justice in California." Water Alternatives 14.2 (2021): 520-545.

— Jonathon K London, Co-Chair, Rural JEDI

Author’s Bio