Keywords: Kantha Textiles, Embroidery, Material Culture, Craft Market, Rural-Urban, Art Practice

Upon the oscillation between domestic production and its inter-consumerist approach, contemporary kantha has transformed its material, material purpose, and utility in many ways. While predominantly, kantha is produced domestically by women with used residual clothes of closed ones, keeping the material memory with elaborate embroidery works outside of commercial purposes. This study locates the practice of modern kantha with its vivid, transforming visual elements and materials (Chatterjee, 2025). Here to re-identify/inform kantha as a significant textile object from the Bengal region of the Indian subcontinent, comprising Bangladesh and West Bengal in eastern India, that contributes to the modern art/craft history of South Asia.

Threads beyond the domestic

Stella Kramrisch (2009) spoke about kantha in its consistent world of pictures:

“The women who design and embroider the Kanthas are free to employ their individual skill in executing any of the possibilities inherent in the theme and the technique of the Kantha.”

The existing scholarships have widely addressed the production and purpose of embroidery in its domestic framework, as women’s generational knowledge and its geographical values are well discussed (Walsh, 2004 & Borthwick, 1984). Kantha is identified with its intimate art history and vivid visual grandeur of needlework, situated in a socio-historical plinth (Zaman, 2009 & Ahmad, 2009). However, in modern kantha the themes and visual elements are subject to addressing the consumer needs, which should be instructed by the NGO workers and designers. Kantha is no longer within the home or the domestic or the women; there are male embroiderers too producing kanthas with diverse techniques for the market (Chatterjee, 2025). On the other hand, discussion emerged considering the artisan-designer dynamics and the agency of artisans in light of kantha made for self-use and for the commercial demand (Modak, 2021). As I take it forward in two ways. I. Identifying the employment and commercial production of kantha by adapting the aesthetics of upcycling in marketable terms noted as upskilling through local fairs, public exhibitions, and community contact. II. Its re-appropriation in Indian contemporary art practice by Indian artists addressing women’s labour and contexts, which have not been studied in the context of kantha production.

Making and the maker

During the second visit to Dolly Paul’s place, Asha Paul, daughter-in-law of Dolly Paul, was washing a 50-year-old kantha (figure 1), which used to be the cover of their treasure box. As it is informed, this kantha is entirely made by reusing used clothes domestically by Sandhamoni Santra, which is in the collection of Dolly Paul, Boinchigram, West Bengal. Prioritising the ethnographic method, here I propose a comparative study by referring to these domestically produced and kept kanthas with the exhibition/fair at Gaganendra Shilpa Pradarshashala, Kolkata, West Bengal. The exhibition (2023) titled “Banglar Nokshi Kantha”, where women kantha makers such as Habiba Mondol from Nadia, Mumtaj Bibi from Birbhum (figure 2) and others across the districts of West Bengal presented and sold their kantha work at the venue, was conducted by/in collaboration with the Folk and Tribal Cultural Centre, Department of Information & Cultural Affairs of the Government of West Bengal. In this exhibition all the kanthas are full of imageries and technical traits (Ahmad, 1997) from the traditional kanthas compiled with the modern accessories.

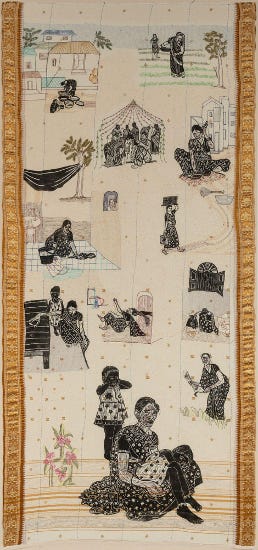

On the other hand, I propose Jayeeta Chatterjee’s practice (figure 3), where she re-took the techniques and aesthetics of kantha/kantha stitches and used sarees (a prevalent women’s garment in the region) collated with the medium of printmaking (a medium of visual production) to create her work addressing women’s labour and stories in terms of contemporary gallery practice. A portal maintained by India Art Fair (2024) has stated about Jayeeta’s work,

“Through cloth scrolls, quilts and prints, the artist documents nuances of working life from homes and communities in Bengal through woodblock prints on saris collected from the very women she bases her works on, and finally overlaid with Nakshi Kantha traditions.”

In a conversation, Jayeeta has addressed that thematically, her works are notations of women’s work/labour and their mundane world of everyday life. The significant approach to identify in Jayeeta’s work is the transforming material utility of reappropriated kantha and the purpose of its production. At this point the discussion introduces the craft-informed practices in gallery spaces that are eventually diverted from their actual usership but acknowledged it in other dimensions within the mercantile interests.

My argument is to locate this alternative thinking through adapting the essence of upcycling and re-appropriating the aesthetics of residue in craft markets and the gallery spaces beyond the domestic.

Residual thinking

This study argues that beyond domesticity, the appeal of contemporary kantha is a proposition that intersects the process of upcycling and monetary involvement of women and women’s labour. It relocates Indian embroidery as a medium that resides at the crossroads of Sondhyamoni Santra, Mumtaj Bibi’s elaborate stitches, and Jayeeta Chatterjee’s kantha-informed artwork (figure 3) that narrates women’s stories extensively in art gallery premises in the urbane. ‘Informing kantha’ situates kantha textiles in a regime of theoretical and practical discussions that intersects the sociology of women's work, transforming craft markets and commercial contacts within the registry of art/craft histories and practices with design studies, sociology, and anthropology.

— Kaustav Chatterjee

Author’s Bio

Connect with us at:

Thanks for reading Just Rural Futures! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.