Migrant Corn: Complexities of changing demographics in the U.S. Corn Belt

Aaron Pacheco, Department of Geography, Indiana University

Keywords: Labor, Migrant, Diaspora, Food

It began as a seed planted in a tilled cornfield in the high plains of Texas. Fully grown, its corn kernels are milled into flour, packaged, and, in this case, shipped hundreds of miles north into the heart of the United States (US) Corn Belt. Commodity chains are complicated and convoluted. Foreign corn surrounded by millions of acres of corn fields — it’s ironic that the greatest corn-producing region in the world imports corn, but corn here is not grown for food.

Most are livestock fodder or ethanol, inputs into secondary industries with greater profit margins. Yet, there is a demand for corn flour, and the end consumer of this bag shares a similar journey.

From as far afield as Mexico or Central America, some even traveled through the same Texas high plains. They all meet here in rural communities of the Upper Midwest Corn Belt as essential inputs to the region's most labor-intensive and profitable industry: manufacturing.

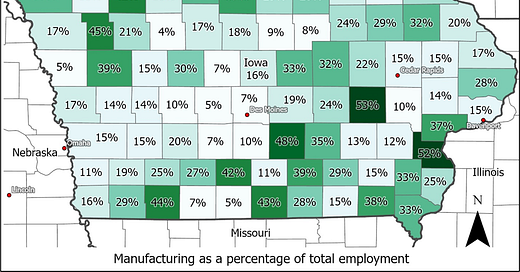

Despite fields as far as the eye can see, corn is less the engine of the Midwestern economy and more its fuel. In the US, corn-based ethanol and animal-based food manufacturing make up the majority of usage, according to the USDA. Flour (let alone just plain edible corn) is miniscule compared to meat and dairy. Gone is the traditional livestock farmer, replaced by high-yielding factory farms, processing thousands of animals in a single facility. To use an astrophysics analogy (because, why not), CAFOs (Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations) placed deep within the Corn Belt act like gravitational wells (black holes), pulling in crops from all sides and dominating local employment (Figure 1).

For decades, stagnant wages, poor working conditions, and the deskilling of jobs were met with high rates of rural-to-urban outmigration and the so-called brain drain. In response to the subsequent labor shortage, employers have turned to a fast-growing migrant workforce to fill this void. Inheriting a dependency on rural anchor employers, the low industry diversity, working conditions, and wages ultimately suppress social and geographic mobility; much of this new workforce lives in precarity.

Our corn flour arrives in Worthington, Minnesota, a small rural town near the Iowa border. Worthington is an example of where the commodity chains of corn, pork, and labor collide. Here, the dramatic demographic shifts of the decades are apparent. Once predominantly white/Caucasian with a small yet relatively diverse economy, according to the US Census, Worthington's Hispanic/Latino population makes up approximately half the total today. The nearby pork processing facility employs nearly one-third of the working population.

One weekday, I stopped for lunch at the small restaurant, Pupusería Crystal (Photo 1). The signature sound of cooks preparing pupusas, thick corn tortillas stuffed with cheese, beans, and deliciousness, echoes from the kitchen. The smell alone transports me back to our family home in El Salvador. The décor is sparse and reminds me more of a cafeteria than a Midwestern restaurant. The building is peculiarly shaped, hinting at a former life as an American diner or fast-food chain. Workers cycle in and out, mostly collecting meals to go. At no point is English spoken during any of my visits. As Worthington's demographics evolved, so did the local economy. Pupusería Crystal and businesses like it make up growing ethnic markets responding to community needs and the changing face of the rural Midwest.

With demographics shifting, so did socioeconomics. Officials have proudly boasted of declining poverty rates and increases in per-capita GDP (Stiglitz et al., 2018). Though GDP may reflect higher productivity, the growing profits of industry grossly outpace local wages. Given such disparity, GDP per capita cannot be a proxy of well-being (Pacheco & Braekkan, 2021). Similarly, declines in poverty at aggregate county or state levels fail to capture disparities in smaller yet growingly denser rural towns (Figure 2). Simply shifting to Census tracts, the higher resolution highlights poverty side-by-side with areas of prosperity. Uneven development leverages a blend of cheap corn with cheap labor to generate profit at different links of long commodity (value) chains.

One can get dizzy studying commodity chains and value extraction. The process remains hidden behind mass retailers and many degrees separating consumers from producers. Even so, the far-reaching effects of global commodity chains on communities are hard-hitting. How can our rural communities, those who feed the nation, gain the social mobility to overcome?

Our corn flour has reached reached its destination. In Worthington, a family prepares dough for homemade pupusas with a traditional chicharrón filling, likely from the nearby pork plant. It's more than food; they are vessels for sustenance, love, and the fruits of labor — And it's not just about migrants, corn, or pupusas. It’s about recognizing who our rural communities are in the American Heartland and giving them voices. It’s about Mexican tortillas, Somali muufo, Rohingya gorur goshto, and even the all-American hot dog. It’s about all of us.

— Aaron Pacheco

Authors bio

Connect with us at:

Thanks for reading Just Rural Futures! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.